I Miss You, George

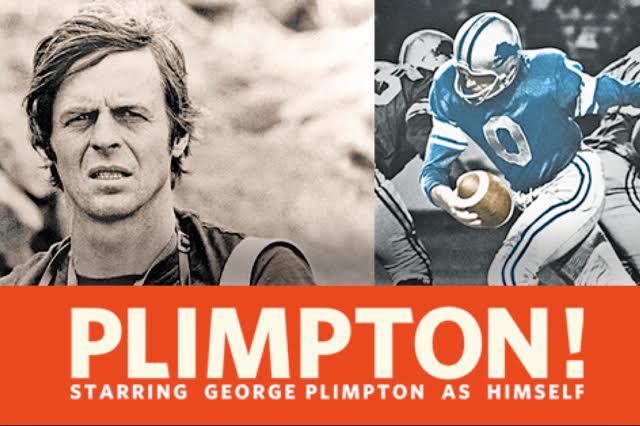

“This is your turf, Jay,” George said, as we navigated the buckling sidewalk on the Lower East side. “I feel a little out of my element.” We were trying to find the bar where we were to give a joint reading, after jumping out of the cab at the wrong spot. At that moment a goth girl with multiple piercings shouted, “Hey George! George Plimpton!” as she passed us. And I realized at that moment that George was never really out of his element, that he was at home, and known, almost everywhere. He was an explorer, and he was an icon, his silver mane and his weathered patrician features as recognizable as his flutey, inimitable accent, that seemed to combine old New York and Cambridge, Mass with a little bit of Cambridge, England. I’ve been thinking about George since I watched the excellent documentary, Plimpton! , directed by Luke Poling and Tom Bean, that recently debuted on PBS.

I first heard that amazing voice over the phone, when I was living in Syracuse, New York, working on an MA in Creative Writing with Raymond Carver and Tobias Wolff and trying to find my own voice as a writer. I was astonished to find myself on the other end of the phone with George Plimpton, who was calling from the offices of the Paris Review, the esteemed literary magazine that he’d been editing since he and Peter Matthiesson started it in Paris in 1952, which I’d been reading since I was in high school. I’d recently sent in a story to the Review and here was Plimpton, saying he quite liked it, but wondered if I had anything else they might look at.

When I hung up I was exhilarated. It was about five PM and I spent the next few hours reading through all of my fiction to date. Imagining Plimpton reading it, I realized that none of it was very good, that it was all derivative of writers that I admired. The only exception was a single paragraph that I’d scrawled on a sheet of paper at dawn a year earlier, after staggering home from a nightclub. It was written in the second person and it began, “You’re not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning, but here you are.” It was just a few sentences, but they struck me as fresh, original and worth expanding upon. I sat down that night and wrote a story that begins in a nightclub, about a guy who was high on cocaine, mourning the loss of his wife and his youthful dreams of success in the city. I called it, It’s Six AM. Do You Know Where You Are. I finished it that morning and sent it off to Plimpton and a few days or weeks later, I can’t quite remember the interval, I received another phone call, this one from Mona Simpson, then an assistant editor at the Review, telling me that it had been accepted.

That story became the first chapter of my novel Bright Lights, Big City, which I wrote the summer after the story was published in the Jan 1982 issue of the Paris Review. Later, after the book was published, I attended my first New York literary party at George’s townhouse on East 72nd Street. George’s house had been the center of New York literary life since the late fifties, when he moved back from Paris. Everyone went to George’s parties, including politicians and movie stars—and always, very good-looking young women, some of whom worked for the Review—but it was the writers who were the stars. That first night I met Truman Capote, Robert Stone, William Styron and Gay Talese. George led me around and introduced me as his latest find. For some reason he’d gotten into his head that I was studying to be a pharmacist before he’d plucked my story out of the slush pile, and he told everyone how he’d saved me from becoming a pharmacist. It was a pretty good story.

George was riding high at that time after the publication of Edie, the brilliant book he created with Jean Stein about Edie Sedgewick and the sixties. I don’t remember his editing on my story but he was certainly a brilliant editor, as Edie so clearly demonstrated. He was also a great raconteur, the best storyteller I’d ever met. We once went to Hollywood to pitch a screenplay together, and he held the studio excess spellbound, despite the preposterousness of the story we were selling. He took me to the Playboy mansion during that visit, though unfortunately Hef’s girlfriend’s mother was visiting so the evening was a very tame one, enlivened mostly by George’s storytelling.

He invented a form of participatory journalism which made him famous early in his career, playing football with the Detroit Lions (an adventure recounted in the best-selling Paper Lion, pitching against an all star team in Yankee stadium, going into the ring against Archie Moore, and getting creamed at golf with Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus. He was a Renaissance Man, and a true man of letters. I don’t know whether he dreamed of writing the Great American novel, like his buddies Mailer and Styron, but I think he lived it. His life was epic. He knew everyone and he tried everything and he went everywhere. And he was an extremely generous friend and editor.

The last time I saw George was a few days before he died in September of 2003, at the Greenwich Village penthouse of literary agent David Kuhn, where we were no doubt celebrating the publication of some book or other. He was as usual at the center of the party, towering over all, surrounded by friends and admirers. We chatted and made a date to have dinner the following week before he left to get to his next party, en route to Elaine’s, where he would eventually have dinner. It was on just such a night, after making the rounds and dining with friends at Elaine’s, that he died, in his bed, a few days later. I think it was an enviable way to go, and as much as I miss him, I’m glad that I can remember him that way, among friends, on his way to the next party.*