Ghosts of New York

The timing was eerie. Last week the Boston Marathon bombings reminded New Yorkers of that day almost twelve years ago when our city was thrown into chaos and our sense of invulnerability shattered forever. And now the apparent discovery of a piece of the wreckage from one of the two airliners that crashed into the World Trade Center, wedged in a narrow alley near Ground Zero, the improbability of the discovery, and of its remaining undiscovered for so long underlined by the fact that the alley is only an inch wider than the seventeen inch width of the fragment. If not for the events in Boston this piece of metal might seem even more like an ancient relic, a reminder of a long ago era, because in recent years the memory of those incredibly vivid days after Sept 11th 2001 has inevitably faded. Unlike Boston, the cradle of the American revolution, New York is not a city that clings to its history. New Yorkers live in the present. As traumatic and stirring as the events of the Sept 11th and its aftermath were for those of us who lived through them, they seem farther and farther away as we go about our business, while the stock market soars and new generations of restaurants spring up like weeds between the cracks in the sidewalk and the so-called Freedom tower rises inexorably, floor by floor, on the site once occupied by the World Trade Towers.

And then this piece of wreckage, this piece of landing gear which failed to land, suddenly appears like Banquo’s ghost, like a disheveled, uninvited guest at our party, to remind us of our history, our scarred-over metropolitan wound, our mortality.

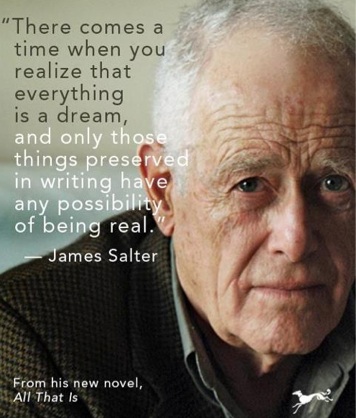

The subject of mortality also hovered over the lawn of a party in Sag Harbor this weekend celebrating the publication of James Salter’s All That Is. The party, thrown by editor Steve Byers, was packed with writers and editors that occupied the front tables of Elaine’s in the 1970s and shifted their headquarters to the American Hotel in the summer. Salter has recently turned 88 and has survived a great many of his contemporaries, including George Plimpton, who was a year younger than the guest of honor, whose absence seemed particularly conspicuous, at least to me, even though he died a decade ago. It was George’s crowd, as well as Jim’s, and his son Taylor Plimpton was there, the youngest guest by at least a decade. George’s friend Bill Becker told me that back in the 1966 he’d passed along the manuscript of Salter’s classic A Sport and a Pastime to George, who’d subsequently published it in The Paris Review.

Anyone who hasn’t read A Sport and a Pastime is strongly admonished to get to a bookstore today and buy it. I’ve reread it every four or five years and I never cease to be amazed by the shimmering magic of the prose, by Salter’s uncanny ability to evoke setting and mood, and—less this sounds precious—his unflinching examination of sexuality. It’s been a while since I read Light Years, his beautiful portrait of an enviable but ultimately doomed marriage, and I think I will have to wait until I finish this latest book, because I suspect that Light Years strongly influenced my novel Brightness Falls, and this novel in progress is a continuation of the story of Russell and Corrine Calloway, the third installment in their story. I’m getting close to the end of the first draft and think I will wait to finish before I return to Light Years. In the meantime, though, I read Salter’s new novel, which has many of the virtues of his earlier work, spanning decades of the life of Phillip Bowman, a former naval officer who becomes an editor at a prestigious New York publishing house after World War II. It’s a book full of beautiful set pieces, which somehow gains weight as it captures the passing of the years and decades. The party in Sag Harbor would have fit beautifully into the book, somewhere near the end, a fact which could hardly be lost on Salter, who seemed as wry and skeptical and observant as he was when I first him almost thirty years ago. I wonder whether, had he written the scene, he would have chosen to have set the party on the very day that most of the guests would have opened their New York Times to find a stellar review of the novel being celebrated.

—Jay