Happy New Year

No less than the farm, the city has it seasonal rhythms, although here the autumn, rather than the spring, is the season of rebirth and renewal: the time to shake off the torpor and idleness of August, the season of openings—of plays, restaurants, galleries, the season when the big books are published, the fashions of the following year unveiled on the runways, the big charities hold their benefits as the gingko trees turn yellow, Fashion Week giving way to the Film Festival and the big gallery shows in Chelsea, the opening of the Metropolitan Opera and the City Ballet and the art auctions at Christie’s and Sotheby’s and Phillips de Pury which will tell us how rich the rich are feeling this year. Even for those who aren’t Jewish, the new year in New York begins in September. A certain tribal anxiety also, a collective memory of September 11th, and of financial panics past, but we’ve made it past that again this year. Another eerily clear day and clement day.

Much as I love the city in September, precisely because I love it so much, I spent most of the month in Long Island, working on the novel, though I did go in to see the revival of Einstein on the Beach at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, one of the most incredible spectacles I’ve ever seen on stage. Glass’s music continues to impress, but that’s been accessible to all since 1976, when it debuted. The great revelation, even for those of us who have seen some of his other work, were Robert Wilson’s tableaux and his staging, the compositions, the lighting, and especially the repetitive, dream-like gesture and motion. Einstein has been hailed as the high point of a certain period, the masterpiece of a collective aesthetic hatched in downtown New York in the seventies, but it still seems utterly fresh; we still haven’t caught up with it.

Also came in to town, for David Salle’s 60th birthday party at Saraghina in Brooklyn, which was packed with the artists, writers and gallerists who are David’s friends. We were all asked to write proposals for David’s autobiography and he asked me to read them to the company. Oddly—one suggestion was “Subjectivity” and another “Objectivity.” Someone scribbled a bunch of squiggly lines which looked like a Cy Twombley sketch, though obviously Twombly wasn’t in the room. Pretty much everyone else was. Originally I was told I wasn’t on the list, and had to talk my way in to David, who eventually vouched for me. My proposal was “My Life in Three Panels.” You know? All those triptychs he paints? I liked Judy Hudson’s title: “I Wish I Could Paint Like Judy Hudson.”

My novel proceeds. At least I’m past the halfway mark. After a weekend trip to California for the Hearst Castle benefit, where we raise money to restore some of the thousands of artworks in the castle—something the state of California doesn’t consider part of its stewardship—I’m hunkering down again out in Sag Harbor, though I will be coming in to do a Q and A with Moshin Hamid, the great Pakistani novelist, tonight. I met Hamid in Jaipur, India last year at the annual literary festival. His new novel, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, is a kind of satiric Pakistani Horatio Alger rags to riches tale, presented in the form of a parody of a self help book.

The massive southern migration of baitfish and predator species south along the east coast is well underway and I’ve been out on the water off Montauk Point several times with my guide Matthew Miller. My first trip out we had a great afternoon—five big bass and eight or nine false albacore. The striped bass is probably the most prized game fish on the Eastern seaboard, pursued by surfcasters and eel danglers and trollers dragging giant umbrella rigs of lures offshore as well as us fly fisherman. It’s the object of a cult and the subject of many books and it’s one of the tastiest fish in the ocean. The false albacore, on the other hand, is virtually inedible, but it’s one of the fastest and pound for pound strongest fish in the ocean. It looks like a cross between a tuna and a mackerel; shaped like a torpedo with retractable dorsal fin and according to Matthew is capable of swimming up to seventy miles and hour. Catching an albie on a nine-weight fly rod is about as exciting as any kind of fishing I know. You cast to individual fish on the surface when they are feeding, usually on anchovies, and retrieve your fly as fast as you can. Once you hook into an albie you have to keep your hands free of the reel since he will usually unspool a hundred or two hundred yards of line in a matter of seconds and bloody up your knuckles if they’re not clear.

Keith Richards incomporable Life has called forth an avalanche of rock and roll biographies (not to mention the scandalous Mick the Wild Life and Mad Genius of Jagger, by Christopher Anderson which I read in one sitting) and I’ve been trying to keep up. Read Greg Alman’s My Cross to Bear confirming that Greg really took a lot of drugs and now deep into Neil Young’s Waging Heavy Peace. Neil Young really is as strange as we always suspected. He goes into his Lionel train obsession about as deeply as Keith went into guitar stuff. Leonard Cohen up next.

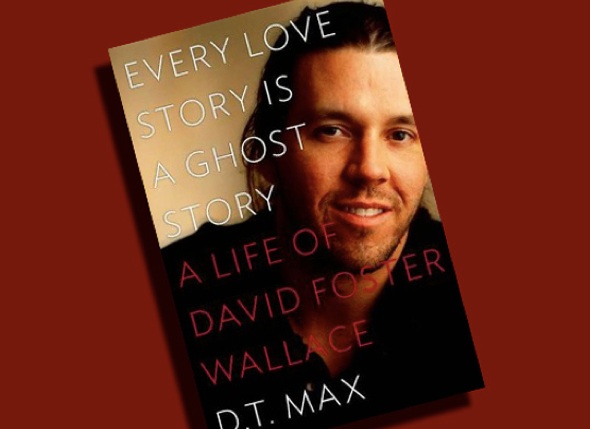

I’m halfway through D.T. Max’s biography of David Foster Wallace, Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, which I misplaced for a month or so; somewhat eerily, I find myself in it. I spent about a month with Foster Wallace at Yaddo, the writer’s colony in Saratoga Springs, in 1987. He’d just published Broom of the System which I’d read. He was a strange, shy, but obviously brilliant twenty three year old. We played tennis—he usually beat me—drank and talked about our work in progress. He was incredibly earnest, but he also had a wicked sense of humor. We’d both majored in philosophy, he at Amherst and me at Williams. He was writing Westward the Empire Takes it Course, his logorreahic, metafictional sendup of metafiction, which I read in pieces, and I was writing my third novel. According to Max, “Wallace admired the older novelist’s control of voice, and also how he could work after a long night of drinking.” I don’t recall the drinking being very heavy—we were all there to write, after all, but then Wallace was by his own admission much more of a pot smoker. Tonight I will probably discover how he felt about my review of Infinite Jest.

—Jay